Continued from the Home Page:

"He was pretty good at a time when driving a race car was a pretty rugged thing."

The short old man walked with a jerky, painful limp. He'd had it since 1949, when he was thrown from a midget during a race in Macon, Illinois. Ben Chesney had half an inch of stagger in his hip ever after.

The crowd watched in horror that May day as Chesney was flung to the dirt from his tumbling car and then slammed hard by a following car. The red flag flew.

The field skidded to a halt. In fearful silence, Ben was scraped off the track and loaded into an ambulance.

After two decades of barnstorming midget tracks across the Midwest, Chesney's professional racing career was over. His neck, two ribs and a collarbone were broken. His left hip was split in two at the socket. He spent four months hospitalized in Decatur with his legs in traction while the pieces of his pelvic bone fused. He returned to St. Louis laid out in a railroad baggage car and covered the last couple of miles to his house in a hearse.

After six months in bed he started walking but needed crutches for another six months. When he healed, his left leg was shorter than his right. While he had to give up racing midgets, he didn't forsake life.

At age 89, Chesney still rode a motorcycle. To him it wasn't a big deal. He had ridden motorcycles through Mexico dozens of times. He once rode an antique Indian from Alaska to St. Louis and then Panama. When he was 80. The words “El Viejo Cuidadoso, “ Spanish for “The Careful Old Man," were painted on the front of his helmet.

It had been half a long and lucky lifetime since Ben Chesney's handsome and athletic young face smiled in victory lane before a roaring crowd. In his world, however, he was still a celebrity as he approached 90. His dapper mustache and quick tongue were regular and popular features at Rex's Cafe, a cozy corner saloon and restaurant in South St. Louis.

Chesney visited Rex's just about every day, wearing matching khaki shirts and slacks. Waitresses kept Ben's coffee warmed, creamed and stirred all afternoon. He could forget a name or a date and could no longer remember much about the few old racing photos he kept in a file drawer. But when he got on a roll he could tell you the price of gas in Acapulco in 1964 or the length of the connecting rods in a four-cylinder Durant.

When asked about racing midgets in the '30s and'40s, his eyes flashed and his wrinkled face broke into a broad smile. "l don't remember how many races I won but I still remember the night I won my first feature. It was in Kansas City, I think, in 1934. I earned $106," he said. “l had a Pierce-Arrow convertible for a tow car. I drove all the way back to St. Louis, holding that $106 in my hand so I could look at it. I thought I was a millionaire!"

Economics, circumstances and wanderlust had deposited Chesney in St. Louis in time for the opening of Walsh Stadium, which hosted midget races and sellout crowds in the years before and after World War II.

Chesney was born in Maryland in 1902, the son of a can factory steam engineer. The plant closed after World War I so the family moved to Philadelphia. In high school Chesney trained to be a machinist but had little success finding work after graduation. In 1922 he and a friend left Philadelphia in hopes of reaching the land of opportunity – California.

"There was a big railroad strike going on and we thought we'd scab in rail yards on the way to California,” he said. The pair passed through St. Louis but got only as far as Oklahoma. Mob violence prompted reconsideration of the wisdom of employment as a strike replacement worker.

The pair high-tailed it back to Philadelphia but launched another run at California in 1923. This time they braved the plains and desert in a 1918 Dodge roadster and arrived in Los Angeles only to fail in all efforts to find steady jobs. After three months Chesney and his companion bought motorcycles -- a 1917 Harley-Davidson and a 1918 Indian -- for a total of $45 and rode back to St. Louis. Their tires touched no pavement between Victorville, California, and Maplewood, Missouri, just a few blocks west of St. Louis.

Chesney decided to stay in St. Louis. The city’s 30 railroads produced a steady supply of freight-yard work and he found an abundance of friendly motorcyclists. He supplemented his income by running an occasional motorcycle race until the early 1930s, when midget racing entered his life.

“I saw a sign advertising midget racing on Tuesday nights at Walsh Stadium and went looking for a job as a driver. I pushed off cars for three or four nights before I got to drive," he recalled.

He discovered that a decent driver could win $30 or $40 a night in tough times when a good mechanic might earn $25 a week. So Ben built his own car.

“It was a poor example of engineering,” he said. "It was based on an Austin American. It had a little 45-cubic-inch engine and a three-speed transmission. I couldn't beat anybody but I could outlast almost everybody."

The little Austin took him to his first feature victory on a night when plenty of more powerful cars couldn't deal with unusual track conditions. The race was held on a flat baseball field soaked by rain.

"To keep their motors going the rest of 'em had to tear around the top of the track, spinning their wheels and throwing dirt out of the place," Chesney said, leaning over his table at Rex's. “I could stay down on the bottom in the turns and motor right under them.They'd whiz by me at the end of the straightaway and every time I'd make it up in the turn. But on the last lap I only had to hold the lead until the middle of the straight, where the finish line was. And I did."

Shortly thereafter Chesney got a career break when another St. Louis driver got hurt in a crash, temporarily opening the seat of a first-class car.

“I think the guy's name was Lou Walker. He tangled with Clyde Dillon and I got to drive his car for two or three weeks. That was my first real race car. All the rest was trash. After that I didn’t have any trouble getting cars," he said.

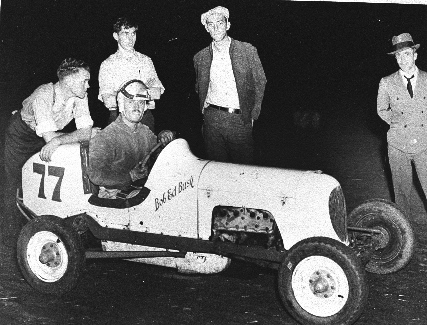

In one of Chesney's oldest racing photos he looks lean, mean and hungry while sitting in

Back to top of page

a knobby-tired midget wearing a metal construction hard hat. Times were hard and racing was a viable alternative to the measly jobs many men felt fortunate to have.

“You could race seven nights a week if you wanted," Chesney said. “I made as good a living as the average mechanic and enjoyed it a lot more. I had a helluva good time in my day.

Tracks in Kansas City, Memphis and all over Indiana and Illinois were within driving distance of St. Louis. I was the track champion in Memphis three years before anybody in St. Louis figured out where I was going on Wednesdays. Then about twenty of 'em started going down."

One of Chesney's racing buddies was another St. Louis motoring legend, the late Ed DeBrecht. They met about 1937, when Chesney was running a midget powered by a two- cycle Elto outboard. DeBrecht, who later became a successful import car dealer, was mechanic and part owner of another midget.

"He was pretty good at a time when driving a race car was a pretty rugged thing. Those guys were hungry. Times were tough. Things were far more fierce than they are today and a lot more risky, too," DeBrecht said in 1989.

"There were a bunch of drivers and mechanics who thought they were really hot stuff. Ben was just one of the guys. His language was more colorful then but one of his wives straightened that out.

" A mutual interest in imported and unusual cars created a lasting friendship. "We both fooled with cars," DeBrecht said. "He had a couple of Cords and at one time used a Bugatti for a tow car. That thing's probably worth half a million dollars now."

Chesney was a sharp mechanic but maintaining the old midgets was a relatively simple task, he said. "Things didn't cost much and we didn't have to do much to the cars. We found out you could pick up 500 RPMs just by balancing the engine. A lot of us were running little Chevy engines. One time somebody found out the rods from a four-cylinder Durant would fit a four-cylinder Chevy but were 3/8 of an inch longer. That really boosted the compression. Too much, really. A lot of times people found their crankshaft on the ground, so we cut that out."

In his day drivers didn't worry much about car setups. "You didn't adjust the car, you adjusted the driver. You went around the track different ways to see how the car went. You'd go in high then you'd go in low. Then you'd go in head first or back off to find whichever way was fastest. Then you'd come in and say ‘This son of a bitch won't steer!'" he said with a laugh.

"We didn't change tires or anything else. We'd buy a midget tire for $7 and run it as long as it had tread. You didn’t have a tire for this track and that track – you just had a tire.”

He doesn’t remember even moving weight around in the car. "l guess we could have," he said thoughtfully, "but nobody ever did."

During Chesney's day, before television kept people at home every night, midget drivers were what he calls "medium celebrities."

"If people found out you were a midget driver, they'd want to go out and look at your car. They'd come back in and say, 'Oooh, that's nice.' We never had no strikes against us, no matter where we went."

Walsh Stadium seated more than14,000 spectators. Chesney said he can't remember a Tuesday night when tickets, $1 to $2 in the later years, weren't sold out. Purses ran into thousands of dollars after the war. "If you showed up after 7 o'clock you couldn't get in the place. Most nights we'd have about 40 cars. Only 24 got to run. The money was very, very good," he said.

Ben knew he ran against the biggest stars of the era but remembered few of their names. One of his career highlights was taking an Offy to Salem, Indiana, in the last big race of a season following World War II

"Every big shot in the country was there, everybody who had run Indianapolis or was going to. Pat Clancy in Memphis owned the car. When I took it back to him and told him I ran fifth he said, ‘Boy, that's great,’” Chesney said. "Over the winter a bunch of people told him how he ought to change the car. He changed everything on it and (expletived) it all up. The next spring we took it back to Salem and all the big shots were there again with every new car in the country. I ran ninth.

"When I got back to Memphis, Pat asked why I only ran ninth. I told him, 'Because nobody would wait for me!' He fired me.

"Chesney recalls that the camaraderie of the road then, like now, was part of racing's allure. "You could go someplace like Macon and know everybody who was there. If you needed a tire or something, somebody would let you use it. We didn't travel together, but we'd meet on the road and stay in the same motels. We didn't care who won as long as we made enough money to get something to eat and get to the next track. Very few of us took our families with us. Not necessarily because we couldn't afford it, we just didn't."

Some drivers used their highway freedom to dabble in babes and booze. "Some of them got so drunk it'd be two o'clock the next afternoon before they came to, then they'd get up and drive to the next race. They figured on riding and getting drunk, riding and getting drunk. I didn't have anything to do with that."

DeBrecht was certain that Chesney's clean habits were responsible for his longevity and health. "He kept active and didn't smoke and never did drink. He never made a big deal about drinking, he just didn't care for it."

If Chesney had a weakness, DeBrecht thought it was fish sandwiches. "I don't know how many times I've heard him ask waitresses for ‘one of them square fish without eyes.’”

Still, it was a wonder Chesney remained sprightly at the age of 89, given the wear and tear on his body. Before his career-ending mishap he had incurred a fractured skull, another collarbone break and a smashed foot which cost him a toe. Not to forget a broken nose.

“One of the places we ran in Memphis was a high school stadium that had concrete steps coming all the way down onto the field. My car hit the steps and the back end started coming over. I flattened my nose on something. I got it bandaged up and came back from the hospital to run the feature. I had to -- I needed the money," he said.

For many years he raced wearing a football helmet, figuring it provided more protection than the hats that passedfor racing helmets in those days. He briefly earned the nickname "Bare- foot Ben" when a collision at Walsh Stadium threw him out of his car and shoes.

“Not many people got killed in midgets but people got banged up a lot. In them days we didn't have no rollbars. There was no place to go if the car tipped over, except to get smashed down in the seat. And there wasn't much room in there, either.

“Many times I went to the hospital just toget patched up," he said. “People ask me why I'm in good shape at my age. I tell 'em that it's because I went to the hospital so many times to get fixed!”

He also credited his longevity to a willingness to settle for second place when it made sense. “I never was a rough driver. I used my brains. I saw what could happen if you weren't careful. Just because you're sitting in a race car doesn't mean you're a race car driver. A lot of people's brains didn't work so fast."

"We always called Ben 'Featherfoot,” DeBrecht said. "He was a money-maker because he never tore up the equipment. A lot of guys who went like hell ended up putting it all back in the car.”

Chesney was considered a racer’s racer during an era in which the St.Louis newspapers actually covered weekly racing. Still, clippings from the prime years of Walsh Stadium (razed in 1956) often lumped him in a concluding paragraph with the other local racers who competed. The headlines went to the national figures passing through town -- Johnny Parsons, Jud Larson, Troy Ruttman, Duke Nalon, Duane Carter and Sam Hanks.

“I was second class to them. They had the best cars. We just had what we had," Chesney said. But, he insists, he didn't mind. "l never had no ambition. I was making a pretty good living driving midgets.

" Surprisingly it was not difficult for him to give up racing after his terrible accident.

"Midgets were losing ground. Track promoters found out the stock car guys would race for trophies. You couldn’t make money driving anymore."

For a few years Chesney worked as an official of the St. Louis Auto Racing Association, helping keep midget racing alive through difficult days. At times he took trophies from his own collection to the track so the struggling association would have some to award.

He has only one trophy left, he said. “I never polish it and it is completely black. That means it's good silver plate. We raced just for the hell of it. People who race now try to be scientific. I went to one race last year. I don't care for the way race cars look now. They look like airplanes with the wings taken off, the drivers all strapped in with iron bars all over their heads."

Winged sprint cars went straight to the bottom of his list. "The ones with the doors on top really look ridiculous".

In 1991 Chesney had been married for 12 years to his fourth wife, Leeta, who was 29 years his junior. After racing he earned his keep doing auto repair in a shop he closed in 1967.

He was still tinkering with his own wheels, a fleet consisting of three Renaults, two Peugeots and a Honda motorcycle. He had his eyes out for another Indian motorcycle.

He spoke with the satisfied air of a man who, like few others, made a long life out of doing whatever he damned well pleased and doing it pretty well.

"If it came around the same way, I'd do it again. Racing was the thing to do in those days and I did it. Most of the people I raced with are dead. They say God takes care of drunks and fools. Well, I don't drink."

Every now and then he shared his racing clippings with friends at Rex's Cafe. Someone asked to borrow a few and Chesney brushed off a promise to get them back right away. "Hell, I'm not going to need 'em much longer."

A question came from the next table. "How many features do you think you won, Ben?"

“I've got no idea," he said. Then he glanced at a tattered piece of newspaper.

"You know, I'll never forget the first feature I won. I came back from Kansas City with $106 in my hand . . . "

Ben passed away in 1994.

###

RickStoff@MotorCoMag.com

BACK HOME